A Little Christmas Music: Saint-Saens's Christmas Oratorio

At Mass on each Sunday of Advent, many parishes light a new candle on the Advent Crown. This year, Five Books for Catholics is doing something similar. Each week it recommends a book for the season and delves into it. You may also want to check out last year’s recommended readings for Christmas and Advent.

Five Books for Catholics may receive a commission from qualifyng purchases made using the affliate links in this post.Last week’s book was on the iconography of medieval and Renaissance paintings of the Nativity. Music is another staple of Christmas. There are popular secular songs, such as Jingle Bells and “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” that radio stations have on loop at this time of year. There are equally popular yet more spiritual carols. There is also a wide range of outstanding classical music for Christmas. Much of it was written for the Church. Some was written for the concert hall, while retaining its roots in sacred music or local carols. For a sample, check out last year’s selection. It proposed five pieces of twentieth-century classical music for Christmas, each from a different country.

This year will stick to one work. The country selected is France, as a homage to St. Bernard of Clairvaux. His Sermons for Advent and the Christmas Season are a spiritual treasure chest for the whole liturgical period and were recommended as the first thing to read for Christmas. You can read more about them here. As a nod to this great doctor of the Church, it seemed fitting to select a French classical music.

Here, nineteenth-century composers have much to offer.

The most obvious choice is Hector Berlioz’s grand oratorio L'enfance du Christ.

There are also beautiful miniatures, such as Adolphe Adam’s “Minuit, chrétiens,” better known to anglophone audiences with a different set of lyrics as “O Holy Night.” Unfortunately, most only ever hear a mawkish rendering of the hymn in which often the soloist is more intent on belting out the high notes with bravura than leading listeners to contemplate the Child of Bethlehem. A performance by unaccompanied choir, such as that of L’Offrande Lyrique, not only resolves the prima donna problem but sounds more like a Church hymn.

Somewhere between Berlioz’s enormous oratorio and Adam’s hymn stands the work chosen here: the Christmas Oratorio of Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921).

Like several other leading French composers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—such as Charles-Marie Widor, Marcel Dupré, and Olivier Messaien—Saint-Saens was a professional organist. The organ features prominently in the work he considered his finest, Symphony no. 3 in C minor, and in the Christmas Oratorio.

In April 1857 Camille Saint-Saens was appointed chief organist at one of the main churches in Paris, La Madeleine. He served in that role for twenty years and was succeeded by his student, Gabriel Fauré. Most of his sacred music, including the Christmas Oratorio, was composed during his stint as chief-organist of La Madeleine. Andrew-John Smith’s recordings of Saint-Saens’s organ music collects the pieces written for La Madeleine (vol. 1), (vol. 2), (vol. 3).

At the time, La Madeleine was the parish of choice for Parisian high society. The offices for the major feasts—such as Christmas and Easter—drew in large congregations. Indeed, Saint-Saens’s Oratorio de Noël op. 12, written in 1858, shortly after his appointment to La Madeleine, is meant for such a service. For the text, it uses antiphons from the Christmas Vigil Mass and the Mass at Dawn. Those antiphons are largely biblical texts. Unfortunately, many of the congregants preferred sacred music of the more theatrical kind and found Saint-Saens’s compositions for the church too austere.

The sobriety of his sacred music attests to the conscientiousness with which Saint-Saens approached his duties a church musician. Though he was not a believer, he did believe in writing music suited to the function.

The early version called upon a string quintet for instrumental backing. Modern performances follow the published version of 1863, which is for soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass, choir, string quintet or orchestra, organ and harp.

The verdict of Jules Pasdeloup, a leading French conductor of the day, was, “Why this is Bach!” High praise indeed, we might think. It was really a put-down. In Paris, then the world capital of opera, Bach was still considered a rather boring, outdated, academic composer. Saint-Saens knew better. Probably because he was an organist, he appreciated that Bach’s works for the instrument were the pinnacle of its repertoire. However, Padeloup’s verdict was not far off in one regard. The score describes the prelude as written dans le style de J. S. Bach. Some commentators conclude, therefore, that the prelude is modelled on or evokes the Sinfonia that opens Part Two of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. Others doubt whether at that stage of his life Saint-Saens was familiar with that work.

Overall, though, the work is French in style. The melodies are long and lyrical. The work unfolds through the evocation of mood and the juxtaposition of contrasting passages rather than through more dialectical development of the themes. The Benedictus is a good example.

Much of the work’s appeal lies in its overall simplicity, sincerity, and intimacy. It opens as a pastorale and gives expression to the simple faith of the shepherds who are evoked at the start. Whereas other composers, such as Rossini and Verdi, were writing sacred music as if it were to be performed in the opera house, Saint-Saens dials down the theatricality in favour of a more meditative tone.

Nor is the work devoid of drama. The prelude passes through a moment of uncertainty that may hint at Herod’s impending persecution of the newborn Jesus or Christ’s future suffering. The rejection that Jesus must endure comes to the fore in the chorus “Quare fremuerunt gentes?” (“Why do the nations conspire and the peoples plot in vain.” Psalm 2). To the repeated question, “Why?” (Quare), the chorus responds serenely with the minor doxology: “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning is now and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.”

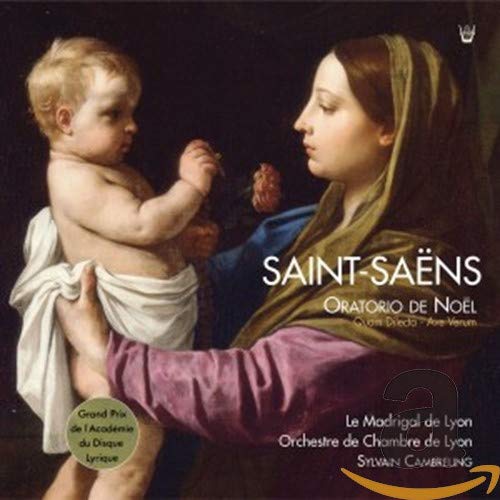

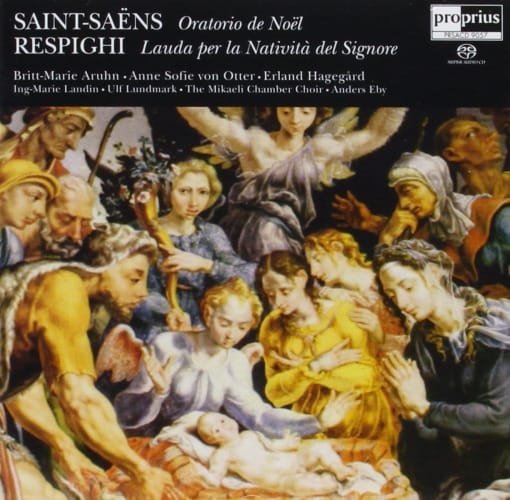

Curiously, Saint-Saens’s Christmas Oratorio has been recorded relatively little compared to other works of classical music written for the season. One good recording is that of the Mikaeli Kammarkör and soloists under Anders Eby. Another, perhaps even better, comes from Le Madrigal de Lyon and Orchestre de Chambre de Lyon under Sylvain Cambreling.

Hopefully, this disarmingly beautiful work will help you enter the Christmas mood.