At Mass on each Sunday of Advent, many parishes light a new candle on the Advent Crown. This year, Five Books for Catholics will do something similar. Each week it will recommend a book for the season and delve into it. You may also want to check out last year’s recommended readings for Christmas and Advent.

The book recommended this week is The Nativity: Themes in Art

by Jeremy Wood.

In last week’s post, the recommended book was St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons for Advent and the Christmas Season. This is an excellent resource for spiritual reading during the season. It unpacks the mysteries of Christ’s birth in the context of the liturgy.

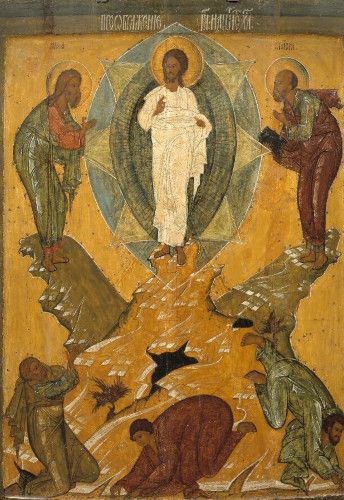

However, the Word of God reaches us not just through our ears but also through our eyes. The Incarnation makes visible the invisible God. Sight is just as much a part of who we are as hearing. So, it too plays an integral role in our worship and sacred art is an integral part of the liturgy. We worship not only through our response to the Word of God proclaimed and preached in the liturgy. We also need to contemplate and worship Christ with the aid of sacred art.

Indeed, sacred art is particularly relevant at Christmas.

"The production of representational art...is quite in harmony with the history of the spread of the gospel, as it provides confirmation that the becoming man of the Word of God was real and not just imaginary."

Second Council of Nicaea

At Christmas, we celebrate the mystery of the Incarnation. One of the main reasons the feast spread throughout the whole Church during the fourth century was to reassert the Christ’s divinity in response to Arianism. However, at Christmas we confess that Jesus is both true God and true man. Whereas Arianism contested his divinity, iconoclasm downplayed his human nature. Iconoclasm claimed that pictorial depictions of God, the saints, or scenes from the Gospel were illicit. That was an unfounded charge if the Son had entered visibly into the world through his Incarnation. The Second Council of Nicaea (787), therefore, condemned iconoclasm as incompatible with faith in the Incarnation. It taught instead that sacred art is an implication of the Incarnation and an important testimony to it. Sacred art “provides confirmation that the becoming man of the Word of God was real and not just imaginary.” The images of Christ, Mary, the holy angels, and the saints draw us “to remember and long for those who serve as models, and to pay these images the tribute of salutation and respectful veneration… Indeed, the honour paid to an image traverses it, reaching the model; and he who venerates the image, venerates the person represented in that image.”

Christian sacred art is rooted in the mystery we celebrate at Christmas: the Incarnation. That is why it becomes particularly relevant at Christmas.

Perhaps that is why so many set up a Nativity scene at their home for Christmas. Maybe they are not just decorating the house for the festivities. They understand that in the Child of Bethlehem we look upon God himself and thereby experience his closeness to us.

For these reasons, you might consider selecting and using a painting of the Nativity for prayer over the coming weeks.

Not only are there so many to choose from. In many, there is far more going on than meets the untrained or inattentive eye. So, learning about the iconography of such paintings is worthwhile.

An interesting guide to this iconography is art historian Jeremy Wood’s The Nativity: Themes in Art.

It is not a comprehensive study of how artists of all periods, countries, and school have depicted the Nativity. Rather, it focuses on Western European art from the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries.

Wood is a specialist in Rubens and van Dyck. Hence, Flemish and Dutch masters are the group that receives most attention. These include not just Bruegel the Elder, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt, but also their less well-known predecessors: Robert Campin, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hugo van der Goes. Italian renaissance artists are also well represented.

The book is short—about seventy pages long— to the point, and contains thirty-five colour photos of works discussed. The photos are not optimal in terms of size and resolution but allow the reader to see the points that Wood is making. Higher resolution versions are easy to find online.

Wood concludes the opuscule by noting that, "Artists, by the nature of most of their commissions in the medieval and Renaissance periods, had to be experts in religious subject matter, but they also knew that their job was to make interesting images."

What makes this book particularly interesting is the way in which unpacks the theological and artistic richness of these Nativities.

A good sample is his explanation of the Nativity section of the Portinari Altarpiece (1475-1476) by Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440-1482), “one of the greatest depictions of the Nativity in Netherlandish art.”

As Wood notes, this work performs all the various iconographic functions that Nativity paintings of the period were meant to discharge.

First, it demonstrates that the Word has truly become flesh and dwelt among us. This is in line with Nicaea II’s teaching on the theological foundation and value of icons. Painting the infant Jesus naked, as van der Goes does, was a typical way of illustrating the reality of his human nature. On the other hand, rays of light irradiate from the child and form a star-shape around him on the ground underneath. These illustrate his divinity. But are they rays of light or just some more of the sheaves of wheat that are lying around nearby? The ambiguity is probably deliberate. At any rate, both the infant Jesus’s nakedness and the sheaves of wheat point to a second characteristic function of medieval Nativity paintings: highlighting the connection between Christ’s Incarnation and the sacraments.

As Wood explains:

“It is important too, that Christ begins his sacrificial life at the Nativity, and in some examples the parallel with the Mass can be made very plain. The Christ Child's nakedness is a visual demonstration that he came into the world in poverty, that he assumed human flesh on behalf of mankind, and it provides a reminder that his body and blood are offered up at the Mass. Often the Eucharistic meaning of the Nativity is made explicit by showing the Christ Child lying on sheaves of corn (from which the bread of the host is made). In some fifteenth-century Nativities, artists even showed the Christ Child lying on the corporal, that is, the cloth upon which the consecrated bread and wine are placed during the celebration of Mass, identifying it as such by showing crosses stitched at the corners. Sometimes, too, the way in which the ox nibbles the straw on which the Christ Child lies may allude to the participant at the Mass."

Besides the sheaves of wheat, van der Goes alludes to the Eucharist in other ways. The “vestments worn by the angels, turn the picture into a celebration of a Solemn High Mass,” whereas the scarlet lilies in the vase may symbolise the blood of Christ, shed on the cross and offered up in the Eucharist. Significantly, none of the angels wears a chasuble. That vestment was reserved for the priest offering the Mass beneath the altarpiece and in persona Christi.

As already noted, the ox sometimes has a sacramental significance in Nativities. Even when this is not the case, the ox and ass stabled in the manger are a staple of Nativities, the Portinari Altarpiece included. Why, though? The Gospels never mention them. True, it is reasonable to assume that they may have been there. However, they became a ubiquitous feature of Nativities for other reasons, both apocryphal and biblical.

The apocryphal inspiration was Jacobus da Voragine’s widely read anthology of the lives of the saints: The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum). In its telling, Mary made the journey to Bethlehem atop a donkey, while Joseph brought along an ox to pay the taxes.

The prophets provide the biblical inspiration. A few editions of the Septuagint translated Habakkuk 3:2 as “in the midst of two animals shall you be known.” Some commentators who followed this dubious translation then used Isaiah 1:3 to identify the two animals: “The ox knows its owner, and the ass its master’s crib; but Israel does not know, my people does not understand.”

The ubiquitous ox and ass point to two other roles of medieval Nativities. One was to incorporate the infancy narratives of the apocrypha. Another was typological: to show how the events and prophesies of the Old Testament prefigure the Incarnation and find fulfilment in Christ.

So too does the Portinari Nativity reference both the apocrypha and the Old Testament.

The manger is built on a column from an ancient building. According to one legend, Mary leant against such a column while giving birth. Another significant detail is that Joseph has removed one of his sandals. This references the way in which artists commonly depicted him using his stockings to blanket the newborn babe.

Among the references to the Old Testament is the harp of David engraved above the doorway of the building in the background (maybe the synagogue). This references two Old Testament prophesies. Micah foretold that the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem, David’s hometown. Amos prophesied that the Messiah would rebuild the house of David.

Wood’s book covers many more examples and is an excellent guide to the iconography of Western European Nativities of the period. By deciphering that iconography, he provides tools not just for appreciating a work of art but for contemplating Christ in such icons, and the full scope of the mystery of Bethlehem.