Five Books for Catholics launched at the beginning of January 2023. To mark its first anniversary, there was a review of the previous year’s articles. That survey honed in on five books that had been recommended in more than one interview.

To mark its second anniversary, this year’s review looks at a different side of the service: its growing deposit of articles on Church history.

There are a couple of reasons to do so. On the one hand, during 2024 Five Books for Catholics published several interesting interviews on chapters of Church history. It opened the current year with a couple more: on Chinese Catholicism and Pelagianism. On the other hand, Pope Francis has urged pastoral agents to study the field more assiduously in his recent Letter on the Renewal of the Study of Church History (21 November 2024).

Five Books for Catholics may receive a commission from qualifyng purchases made using the affliate links in this post.Pope Francis states that he wrote the letter out of a concern that candidates for the priesthood and pastoral agents lack a sufficient and “genuine sense of history.” Such a sense, he points out, does not consist in knowing more history but in appreciating our constitutive historical dimension. By nature, we are bound up with our forebears. Hence, the identity and possibilities of an individual or a community are shaped in part by earlier generations. If we do not attend to our bonds with tradition, “all that remains is the personal memory of facts bound to our own interests or sensibilities, with no real connection to the human and ecclesial community in which we live.”

Pope Francis’s argument is similar to one that various philosophers made against liberalism in the eighties. Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, and Michael Sandel criticised liberalism for viewing humans as utterly autonomous, unencumbered selves. Rather, we are social and political animals by nature. We cannot develop without being rooted in a community, with its peculiar customs, beliefs, and history.

In rehearsing this argument, Pope Francis makes a timely warning against wokeism. He warns that, without a proper sense of history, we will ignore some facts, select others, and interpret all according to our interests. We will not seek to “to understand reality as it is” but envisage it “as we imagine it or would prefer reality to be.” Instead, we will be fall into ideologically motivated historical revisionism: the “tendency to dismiss the memory of the past or to invent one suited to the requirements of dominant ideologies”, “the cancellation of past history” and “clearly biased historical narratives.”

Indeed, Pope Francis describes some of the impulses behind wokeism in a citation from his encyclical Fratelli tutti.

“There is a growing loss of the sense of history, which leads to even further breakup. A kind of ‘deconstructionism’, whereby human freedom claims to create everything starting from zero, is making headway in today’s culture. The one thing it leaves in its wake is the drive to limitless consumption and expressions of empty individualism.”

Another problem, he notes, is that many rely excessively and even uncritically on the social and mass media for their view of the world.

At the same time, Pope Francis does not expect us to become simplistic apologists for the Church. Rather, he urges us to acknowledge the faults of the Church and to love her, notwithstanding the sins of her members.

These reflections are pertinent to everyone. It is only in the final section that Pope Francis makes recommendations that are specifically for teachers and scholars of Church history.

First, teachers of Church history should not take a purely chronological or even apologetical approach. Second, Church history should not be simply treated as a secondary moment of theology and thereby become “incapable of truly entering into dialogue with the profound and existential reality of the men and women of our time.” Third, seminarians need to be taught how to read the fundamental texts of Ancient Christianity rather than project on to them anachronistic frameworks. Fourth, Church history should not be studied from a “neutral or sterile position” but with “a personal and collective passion, an engagement proper to those who are committed to evangelization.” Fifth, it should contribute to “the development of an ecclesiology that is both truly historical and sacramental.” Sixth, it should not “cancel” the “insights from those whose voices were not able to make themselves heard over the centuries.” Seventh, it should dedicate special attention to the martyrs because “where the Church has not triumphed in the eyes of the world is when she has attained her greatest beauty.”

Without further specification, a couple of these seven recommendations remain open to both valid and questionable interpretations. Take the fourth one. Some might wonder whether the neutrality criticised is indifference to the mission of the Church or scholarly objectivity and detachment. The former is a defect. However, the latter a virtue and requisite of scholarship. Moreover, who is to say whether a scholar’s research is sterile and lacks a commitment to evangelization? Many might think that a scholar intent upon studying of the changing meaning of the term ‘mystical body’ in medieval theology is not very concerned about evangelization. Yet, Henri de Lubac’s study of that very matter made an important contribution to our understanding of the Eucharist and its role in building the Church, as Richard DeClue explained here.

Perhaps the letter should have formulated an eighth recommendation that makes more explicit a principle that runs throughout it: it is necessary to study the history of the Church in light of the deposit of faith rather than through a secularist lens.

Modernity works with an unduly restrictive concept of both reason and history. The natural and social sciences set the bounds for what qualifies as a rationally or historically verifiable fact. That leaves no place for a history of the Church as the Body of the Risen Christ. It only allows for a history of the Church as a purely human institution that is predicated upon false religious beliefs.

What the secularist refuses to acknowledge is that Revelation discloses the most fundamental historical facts. The Church has spelt these facts out in its dogmatic definitions. Such facts—say, the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and the efficacy of the sacraments—are not discoverable through sheer research. They are accessible through faith alone. Without the necessary grasp of such facts, a researcher, no matter how rigorous, will be wont to see Church history as the outcome of decisions made under a mistaken and maybe even opportunistic manmade ideology.

Even believers can be tempted at times to view the Church through categories of the social sciences rather than the supernatural ones of sacred teaching. That leads to what is effectively a secularist and sociological conception of the Church and doctrinal development.

Pope Francis’s recent letter rightly stresses the importance of knowing the history of the Church. Modesty apart, Five Books for Catholics is a good resource for learning more about Christian history. This is not simply because it shortlists some of the best books on a specific chapter of Church history. Each interview surveys a facet of Church history in one way or another. Take the survey of Anton Bruckner’s sacred music on the bicentenary of the composer’s birth. It brought up Cecilianism, a nineteenth-century movement to reform Church music in German speaking countries. Similarly, Christopher’s Scalia’s discussion of the novels of Evelyn Waugh brings up a historical event that novelist found deeply symbolic yet disheartening: Churchill’s conferral of the Sword of Stalingrad to Joseph Stalin. Waugh saw it as symbolic of Britains abandonment of its traditional values in favour of modernity.

Of course, some articles address Church history directly. Here are five from last year.

1.

In 2024, Five Books for Catholics covered two ecumenical councils: the Council of Florence and Vatican I. In selecting books on the Council of Florence, Fr. Thomas Crean OP explained one of the reasons why he wrote his own study on it Vindicating the Filioque: The Church Fathers at the Council of Florence. He was “struck by the prevailing myths that float around” on Florence “in the ecclesial consciousness.”

“One myth is that there was not any free discussion and that the Greeks were pressured.

Another is that the Latins relied on false patristic citations, were only interested in scholastic philosophy, and made statements that the Greeks did not understand. As a result, there was no real meeting of minds and the union achieved was not genuine.

When I read the Acts of the Council, it was evident that this was not true at all. I thought, therefore, that it would be interesting to write something to show this.”

Nevertheless, the union that Florence achieved with the Greeks was short-lived. In that sense, the Council was a failure. However, Fr. Crean noted that it was an enduring success in two regards.

“First, it defined a portion of revealed truth in a very clear way. Every definition of an ecumenical council stands forever. It is a gift for the whole Church. So, from that supernatural point of view, the council was certainly a success.

It was a success in another regard. Later, it was the benchmark for future reunions that did last. The decree of union that was drawn up was used as the decree for union with Ukrainian dioceses in the late sixteenth century and then with Romanian dioceses.

So, the Council of Florence achieved lasting good, though not exactly the good it was aiming at.”

2.

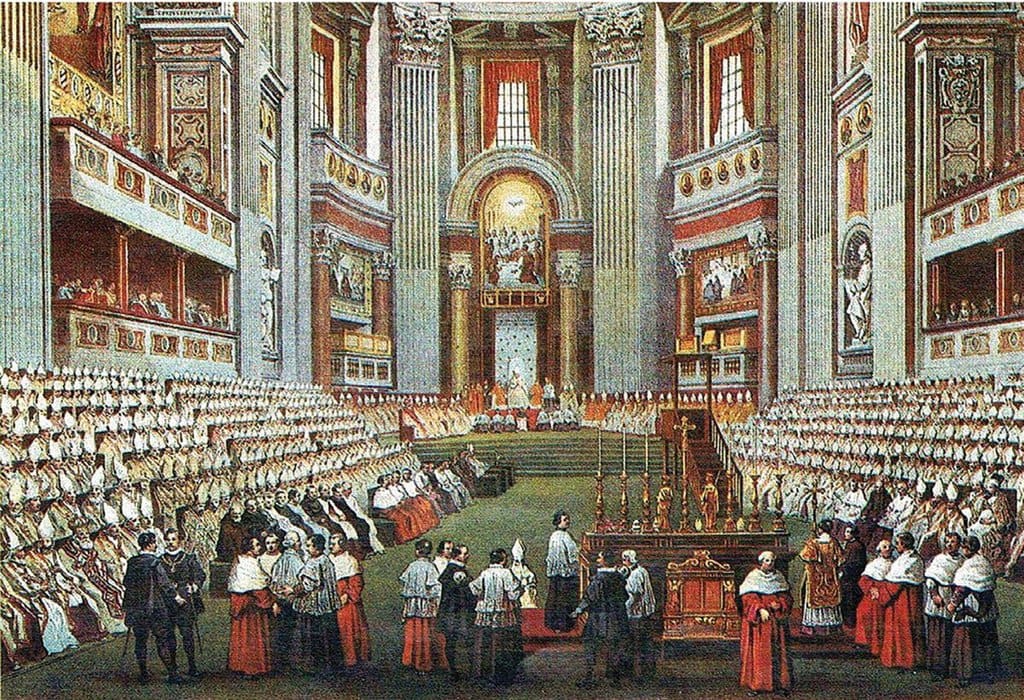

The other council surveyed last year, Vatican I, was also an admixture of success and failure. It was cut short by the collapse of the Papal States and failed to cover all the issues on the agenda. However, the two dogmatic constitutions that it did issue, Dei Filius and Pastor Aeternus, were major turning points for the Church. The former rejected both fideism and rationalism, while clarifying that faith and reason are compatible with one another. The latter defined the dogmas of papal primacy and infallibility.

Moreover, the paradoxical coalescence of success and failure is referenced in the title of one of the studies on Vatican I that Shaun Blanchard selected: Margaret O’Gara’s Triumph in Defeat: Infallibility, Vatican I, and the French Minority Bishops.

The title refers to Charles-Henri Maret’s assessment of Vatican I: “The minority has triumphed in its defeat.” Maret was one of the French bishops who opposed the definition of papal infallibility and primacy of jurisdiction. How then could he claim victory?

As Prof. Blanchard explained, “What the French minority bishops did was apply a certain amount of pressure to force the cooler ultramontane heads to define their position more carefully. In Pastor Aeternus, there is certainly a strong emphasis on papal authority. However, the definition of papal infallibility is very clear and does not fall afoul of what the minority really feared: the proclamation of a papal infallibility that was personal, absolute, and separate.

O’Gara studied their correspondence and their writings exhaustively. She argues convincingly that in the end, partly due to pressure from the minority, partly due to cooler heads in the ultramontane camp, Vatican I’s definition of papal infallibly was neither doctrinally deficient nor erroneous. Though concerned and worried, ultimately the minority bishops were able to reconcile the definition with their consciences. Charles-Henri Maret was able to sign on to the definition in good conscience, as was John Henry Newman.”

Prof. Blanchard pointed to another sense in which Vatican I was a case of triumph in defeat. Vatican I dealt with the fallout from the French Revolution’s dismantling of Christendom. Paradoxically, however, that fallout made it possible for Vatican I to settle the centuries-long debate over papal primacy.

“The… reason the debate could not be resolved prior to Vatican I was that governments did not allow it to be resolved. For example, during the Third Session of the Council of Trent, the Cardinal of Lorraine declared that the theologians of the University of Paris did not hold Lateran V to be an ecumenical council, nor the pope to be superior to councils, and censured as heretics whomsoever held such positions. That was an overstatement of how the University of Paris operated, but the Cardinal of Lorraine had the backing of the French crown. There was a limit to papal power over a cardinal who had the backing of a kingdom as powerful as France.

By the nineteenth century, things had changed. It is not that governments no longer cared about religion or that those governing were no longer religious. Many cared deeply about religion. It is just that the French Revolution had overturned society so profoundly that those governing were no longer conceived in the manner of an anointed sovereign or a Holy Roman Emperor, whose role it was to lead all citizens or subjects to heaven. This is what allowed the ultramontane position to assert itself for the first time and not be blocked by a secular government.

Had ultramontane or papalist theologians attempted to define papal infallibility at the Council of Trent, there would have been a pushback from France, at the very least, and probably from the Holy Roman Emperor and other monarchs too. It would never have gotten off the ground.”

3.

Shaun Blanchard also gave a fascinating overview of the Jansenist controversy. Besides clarifying certain misconceptions about Jansenism, he pointed out that, “We can understand certain important psychological, theological, and ecclesial dynamics by looking at the Jansenist controversy and studying it closely.”

“Right now, there is quite a charged debate in the English-speaking world about papal authority; about the role of bishops, bishops’ conferences, and the laity; about synodality; about the reception of disciplinary and doctrinal decrees. Like any other group of humans, we sometimes feel that we are experiencing something unprecedented. Americans, for example, love to say that such and such a thing is unprecedented in the history of the Presidency. Usually, it is not.

The same might be going on in the Church. The Jansenist conflict can illuminate how Catholics have dealt with these same debates in healthy or unhealthy ways, a productive or unproductive manner.”

“This is a very sad episode in Church history. There were very good people on each side of this dispute, but because of some sinful personalities, personal rivalries, and powerful competing systems (the French monarchy and the papacy), it turned into a regrettable episode.”

4.

Truth be told, two-and-a-bit ecumenical councils were covered in 2024. Michael Dunnigan explained the history, reception, and interpretations of one of Vatican II’s most emblematic and controversial documents: Dignitatis humanae, the Declaration on Religious Liberty.

He noted how, “One of the problems, especially in the United States, is that many conflate Dignitatis humanae with the thought of John Courtney Murray. Murray was an important scholar who made many positive contributions to the document. He also had some problematic ideas. Some of his thought made its way into the document. However, he lost battles on some important issues—especially the relationship between the Church and secular governments—but he refought.”

Specifically, Courtney Murray believed that the teaching of the nineteenth-century popes on the duty of political authorities toward the true religion were contingent and superseded. At the same time, Vatican II did not specify how that teaching applies today.

As Prof. Dunnigan explained, “The traditional teaching on duties of the civic community to God is important and remains intact. However, the council fathers deemed that this was not the most important subject in our day. Rather, they wanted to stress the natural rights of the person.

In the past, other religions seemed to pose the greater threat, but the council fathers felt that unbelief or atheism is currently the greater challenge to Catholicism.”

5.

The main challenge for the Church during the fourth century, on the other hand, was Arianism and its offshoots. Ecumenical councils, such as Nicaea, were one way in which the Church took it on. Hymns were another, as Fr. Brian Dunkle SJ pointed out in his discussion of St. Ambrose.

“One of the fascinating points about the history of song is that, with some exceptions, the earliest surviving non-Scriptural hymn from the Christian tradition is Arius’s so-called Thalia, the wedding song that he composed early in the fourth century. It was a subject of mockery for his opponents. However, it is clear that the rival parties in fourth-century doctrinal controversies drew on music, almost in the way that we might use rallying songs. The different music and language helped distinguish one party from another.

Ambrose never refers explicitly to how his songs are meant to combat others. However, the circumstantial evidence, as well as his own reference to his hymnody as a kind of magic spell, indicates that he was part of this controversy. Other Fathers of the period, such as Hillary and Augustine, engaged in a similar sort of gamesmanship. They too composed hymns to spread orthodoxy and counter their rivals.”

Indeed, it was Ambrose’s hymnody that attracted Fr. Dunkle to study the great bishop of Milan.

“As much as I was taken by doctrinal issues, or the philosophical and biblical background of patristic thought, I believed that there was also much to be found in the verse and popular life of the faithful.

To my mind, no one exemplified that more than Ambrose, even though he was quite learned by the end of his career.

He had read widely in Greek theology and was the conduit for so much theology to the Church of the West.

Nevertheless, he probably expressed himself most enduringly and foundationally in his hymns.

As a personality, he seemed to have so many different parts. This intrigued me and I believed that he captured and pulled together many of those parts in his hymns, which were passed on and were deeply influential on all Western and Latin hymnody.

Initially, I approached him through his songs. Little by little, I grew to know him as a political, theological, and ecclesiastical figure. I find each of these parts infinitely intriguing because of what they show us about the life of the Church and the mind of this genius.”

One of the books that Fr Dunkle recommended is Cesare Pasini’s Ambrose of Milan: Deeds and Thought of A Bishop. Whereas most modern biographies presented Ambrose as an important political player, Pasini rightly stresses that Ambrose was a bishop and his interventions in politics were always pastoral in character.

Another of Fr Dunkle’s recommended books was Robert Louis Wilken’s The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God because it “captures the historical, cultural, and theological milieu” of the Patristic period.

Hopefully, this survey has stoked your interest in Church history and desire to read more about its fascinating twists and turns.