The memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary is celebrated on October 7 in the General Roman Calendar. Moreover, for the last 140 years, the Catholic Church has consecrated October to the Holy Queen of the Rosary. This month, therefore, we might want to do some spiritual reading on praying the Rosary.

The most authoritative writings on the subject are the papal bulls and letters on the Rosary. These go back to St. Pius V. In them, the popes exhort the faithful to pray the Rosary on account of its manifold efficacy. They teach that it secures Mary’s intercession, unites us to Christ in his mysteries, strengthens Christian life, builds up the Church, and transforms society.

Here is Five Books for Catholics’ selection of the five most representative papal documents on the Rosary.

This year there is a further reason to take these papal exhortations to heart, pray the Rosary more intensely, and entrust the Church to Our Lady. During October, Pope Francis is holding the first session of the Synod on Synodality. This event calls for our prayers to Mary, Mother of the Church.

- Consueverunt Romani Pontifices

by St. Pius V - Supremi Apostolatus Officio (Vatican website)

by Leo XIII - Latitiae sanctae (Vatican website)

by Leo XIII - Marialis cultus (Vatican website)

by St Paul VI - Rosarium Virginis Mariae (Vatican website)

by St. John Paul II

1.

Pius V's Consueverunt Romani Pontifices

St. Pius V, pope from 1566-1572, is the one responsible for the consolidation and spread of the Rosary in its current form. No other papal document on the Rosary has had a greater impact than his 1569 bull Consueverunt Romani Pontifices .

First, the Hail Mary in its current form was consolidated during his pontificate. The Hail Mary had developed out of liturgical antiphons that juxtaposed Gabriel’s salutation of Mary, during the Annunciation, with Elizabeth’s, during the Visitation. The invocation entreating the Mother of God to intercede for us sinners was added later on. The Roman Catechism, published at the beginning of Pius V’s pontificate, approves of this addition to the Hail Mary and explains why it is appropriate. It thereby endorses the current form of the prayer, the earliest written records of which come from late fifteenth-century Italy. Before long, this version of the Hail Mary was established definitively across the Catholic world. That occurred, once it was included in the first edition of the Roman Breviary, issued under Pius V in 1568.

A year later, Pius V established and spread throughout the whole Church the current form of the Rosary. He did so in the bull Consueverunt Romani Pontifices. There he endorsed the Dominican method of praying the Rosary and exhorted the faithful to adopt this pious practice.

He explains that the Rosary, or Psalter of the Blessed Virgin Mary, consists of both vocal and mental prayer.

It is a vocal prayer. The Blessed Virgin Mary “is venerated by the angelic greeting [i.e. the Hail Mary] repeated one hundred and fifty times, that is, according to the number of the Davidic Psalter, and by the Lord's Prayer with each decade.”

It is also a mental or contemplative. “Interposed with these prayers are certain meditations showing forth the entire life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, thus completing the method of prayer devised by the Fathers of the Holy Roman Church.”

The bull also reflects on the origin and social import of the Rosary, two themes to which subsequent papal documents will return.

Pius V reports that St. Dominic adopted an already existing devotion and spread it to combat the Albigensian heresy. Three-hundred years later, Leo XIII goes even further and claims that St. Dominic was the first to devise “this new method of prayer.”

Such stories about St. Dominic give the Rosary a more glamorous and saintly origin but only began to circulate 250 years after his death. They embellish extravagantly upon an underlying historical fact. The Dominicans were the main promoters of the Rosary. However, the Rosary developed over several centuries and through various channels, as John Paul II acknowledges at the beginning of Rosarium Virginis Mariae.

In Conseuverunt Romani Pontifices, Pius V initiates a second thread that runs through later papal teachings on the Rosary. He stresses the importance of praying the Rosary for the reform of Church and society. He teaches that, by securing Mary’s intercession through the Rosary, the faithful will combat heresy, secure peace, and convert sinners.

No doubt, one of the wars Pius V was thinking about when he issued the bull was the ongoing conflict between Christian princes and the Ottoman Empire. Indeed, in the run up to the Battle of Lepanto he called on the faithful to pray the Rosary. Little wonder then that he attributed the Holy League’s victory on Sunday, 7 October 1571, to the Blessed Virgin and instituted the Feast of Our Lady of Victory in Rome to thank her for her intervention and commemorate the Rosary.

2.

Leo XIII's Supremi apostolatus officio

In 1573, Gregory XIII changed the name of the feast to Our Lady of the Rosary and set it for the first Sunday of October. In 1913, Pius X switched it back to 7 October to give priority to the Sunday cycle. At any rate, St. Pius V is the one responsible for the current memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary. He is thereby indirectly responsible for the consecration of the whole month of October to her.

The one directly responsible is Leo XIII. In Supremi apostolatus officio (1883), not only did he initiate across the Church the custom of consecrating October to Our Lady of the Rosary. He also issued the first of his twelve encyclicals on the devotion.

The idea of dedicating October to praying the Rosary originated with the Dominican priest, José Peralta y Marques. He wished to boost the life of his parish with more Marian devotion. May offered one occasion to do so, but he wanted another month-long rally of Marian prayer. October was the most obvious candidate. It was the month with a feast dedicated to a well-established and widely practiced Marian prayer, the Rosary, that could be held in common more frequently in the parish over the course of a month. Hence, the idea of dedicating October to praying the Rosary.

Peralta y Marques asked his confrere, Fr. José María Morán, to write a tract in support of this initiative. In that book, The Month of the Rosary: The Month of October (Mes del Rosario o mes de octubre, 1866), made an appeal to the Spanish episcopate to institute this practice across the country. They liked the idea and implemented the initiative.

Leo XIII also liked the idea. In Supremi Apostolatus Officio, he decreed that October 1883 be consecrated to the Holy Queen of the Rosary and the devotion celebrated solemnly in parishes across the Catholic world. The following year, in the encyclical Superiori anno, and made this practice an enduring custom.

"The Rosary, if devoutly used, is bound to benefit not only the individual but society at large." (Leo XIII)

Leo XIII's Laetitiae sanctae

After Superiori anno, Leo went on to issue ten more encyclicals on the Rosary, all except one in the run-up to October (list). Moreover, he did not envisage the Rosary simply as a means of personal spiritual growth. Rather, his encyclicals on the Rosary are one apiece with his major documents on social teaching. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Laetitae sanctae (1893).

Near the beginning, Leo explains that how his own advocacy of the Rosary is part of his efforts to promote the common good and social prosperity around the world.

“We are convinced that the Rosary, if devoutly used, is bound to benefit not only the individual but society at large. No one will do us the injustice to deny that in the discharge of the duties of the Supreme Apostolate we have laboured - as, God helping, we shall ever continue to labour - to promote the civil prosperity of mankind. Repeatedly have we admonished those who are invested with sovereign power that they should neither make nor execute laws except in conformity with the equity of the Divine mind. On the other hand, we have constantly besought citizens who were conspicuous by genius, industry, family, or fortune, to join together in common counsel and action to safeguard and to promote whatever would tend to the strength and well-being of the community. Only too many causes are at work, in the present condition of things, to loosen the bonds of public order, and to withdraw the people from sound principles of life and conduct.”

We might deem it exaggerated to class Laetitiae sanctae and its like as social encyclicals. After all, in Laetitiae sanctae, Leo proposes spiritual practices, not, as in Rerum novarum, specific legislative, institutional, and economic policies.

The popes and Catholic theologians of the period acknowledged that the immediate causes of the existing social problems were political, institutional, and economic in nature. However, they were equally adamant that the deepest causes of those problems were ideological, moral, and religious (see Graves de communi re 11). The insisted that only spiritual remedies can cure social problems at their root. For this reason, a document such as Laetitiae sanctae does form part of Catholic social teaching. Indeed, it is a vital part of that body of teaching.

Leo goes on to identify three prevalent attitudes that, in his view, do most harm to the common good. These are a distaste for a modest, laborious life; repugnance to suffering; and forgetfulness of the future life.

As a remedy, Leo proposes the Rosary. Each set of mysteries helps us overcome one of these socially destructive attitudes. The joyful mysteries make us appreciate the value of a simple life and hard work. The sorrowful mysteries help us overcome our unwillingness to suffer out of charity. The glorious mysteries make us mindful of the future life we should hope for.

4.

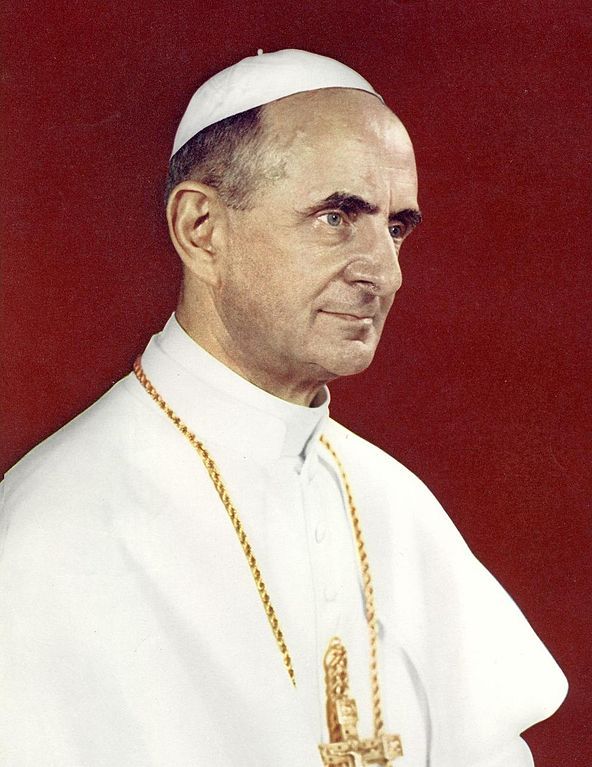

Paul VI's Marialis cultus

Both Pius V and Leo XIII wrote their briefs on the Rosary against the backdrop of the Council of Trent. Moreover, Leo wrote his in the wake of the French Revolution and in response to modern secularization. The next two papal documents, on the other hand, approach the Rosary within the liturgical and pastoral reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

St. Paul VI’s apostolic exhortation Marialis cultus is not on the Rosary as such but on the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It reassesses Marian devotion in the light of Vatican II’s teachings on the Church and the liturgy. As a result, it proposes some principles for a renewal and aggiornamento of Marian devotion.

In the final part of the document, Paul VI turns his attention toward the Rosary. He highlights how it is contemplative, centred on Christ, and deeply biblical. However, his main conribution consists in clarifying its relation to the liturgy.

“Liturgical celebrations and the pious practice of the Rosary must be neither set in opposition to one another nor considered as being identical. The more an expression of prayer preserves its own true nature and individual characteristics the more fruitful it becomes. Once the pre-eminent value of liturgical rites has been reaffirmed it will not be difficult to appreciate the fact that the Rosary is a practice of piety which easily harmonizes with the liturgy. In fact, like the liturgy, it is of a community nature, draws its inspiration from Sacred Scripture and is oriented towards the mystery of Christ. The commemoration in the liturgy and the contemplative remembrance proper to the Rosary, although existing on essentially different planes of reality, have as their object the same salvific events wrought by Christ. The former presents new, under the veil of signs and operative in a hidden way, the great mysteries of our Redemption. The latter, by means of devout contemplation, recalls these same mysteries to the mind of the person praying and stimulates the will to draw from them the norms of living. Once this substantial difference has been established, it is not difficult to understand that the Rosary is an exercise of piety that draws its motivating force from the liturgy and leads naturally back to it, if practiced in conformity with its original inspiration. It does not, however, become part of the liturgy. In fact, meditation on the mysteries of the Rosary, by familiarising the hearts and minds of the faithful with the mysteries of Christ, can be an excellent preparation for the celebration of those same mysteries in the liturgical action and, afterwards, for continuing our recollection of them throughout the day. However, it is a mistake to recite the Rosary during the celebration of the liturgy, though unfortunately this practice still persists here and there.”

Although Paul VI is mainly concerned with centring Marian devotion in the liturgy, he too touches upon the Rosary’s importance within society.

Society and the Church grow out of the family. Their health depends on the spiritual health of the families that make them up. However, a family needs to pray together be in good spiritual health and take on the character of a domestic Church. Ideally, Christian families should pray some of the Liturgy of the Hours in common. Otherwise, “the Rosary should be considered as one of the best and most efficacious prayers in common that the Christian family is invited to recite.”

"If one studies the history of Christian worship, in fact, one notes that both in the East and in the West the highest and purest expressions of devotion to the Blessed Virgin have sprung from the liturgy or have been incorporated into it." (Marialis cultus)

5.

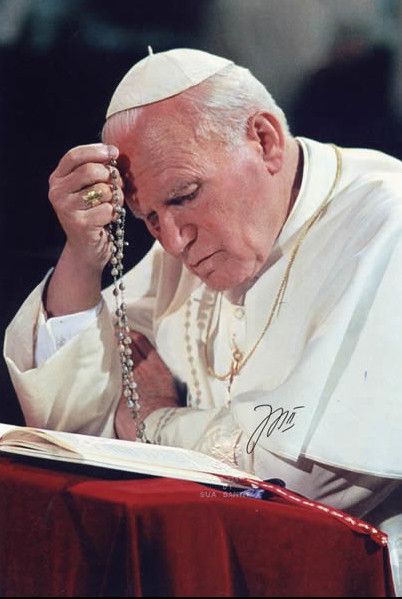

John Paul II's Rosarium Virginis Mariae

Perhaps no pope has evinced such a strong Marian devotion as St. John Paul II. His papal coat of arms represented Our Lady at the foot of the cross. Equally Marian was his papal motto: Totus tuus. It evoked a prayer from St. Louis-Marie Grignon de Montort’s True Devotion to Mary: "I am all thine and all I have is thine, O most loving Jesus, through Mary, thy most holy Mother" (n. 233). Moreover, at the beginning of the pontificate, he described the Rosary as his favourite prayer. Often, he could be seen praying it intensely. Indeed, his testimony was his most compelling teaching about the Rosary. However, there is also his 2002 apostolic letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae.

It was written to commemorate the 120th anniversary of Leo XIII’s first encyclical on the Rosary and to encourage the celebration of a year of the Rosary. It is the most comprehensive papal document on the Rosary and explores all its various aspects. Like John Paul II’s episcopal motto, it is informed by the spirituality of St. Louis-Marie Grignon de Montfort.

The apostolic letter speaks of conformity with Christ eleven times and focuses on how we achieve this conformity through devotion to Our Lady. The source for this teaching (n. 15) is Grignon de Montfort's True Devotion to Mary (n. 120).

In the Rosary, we attain this conformity with Christ by contemplating his mysteries, under Mary’s tutelage. To this end, Rosarium Virginis Mariae encourages the inclusion of a new quintet of mysteries: the mysteries of light. Each one is a key mystery from Christ’s public ministry. They are meant to ensure that the Rosary might truly function as a “compendium of the Gospel” (that phrase goes back to Pius XII’s Philippinas insulas,1946).

This initiative has made the Rosary more spiritually enriching. Nevertheless,it has a downside. As John Paul II was aware, increasing the number of Hail Maries recited from 150 to 200, undermines the Rosary’s symbolic connection to the Psalter and the Liturgy of the Hours. However, he believes that this increase in “Christological depth” outweighs the loss of its symbolism as the Psalter of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

In his defence, it is also worth noting that the linguistic barriers to praying the Liturgy of the Hours that gave rise to the Rosary no longer exist. The Rosary originally developed as a substitute for monks who did not know the Latin needed to pray the hours. Nowadays, Latin Rite Catholics can pray the Liturgy of the Hours in the vernacular. The Rosary’s symbolic connection to the Psalter is no longer as necessary or important. Rather, as Paul VI stressed, the Rosary supports the liturgy by preparing us for the celebration of Christ’s mysteries and keeping our mind fixed on them. John Paul II’s inclusion of the mysteries of light strengthens this liturgical role of the Rosary.

Conclusion

These five papal documents on the Rosary remind us that the Church depends primarily on God's action, not ours. For this reason, we must rely primarily on grace, not our own efforts; on the liturgy, not our own initiatives; on prayer rather than praxis; on the Mother of the Church rather its sinful members. They are eloquent expressions of the Marian dimension of the Church.

At the same time, they are a perfect example of what Benedict XVI called the hermeneutic of reform. There is remarkable continuity in the teaching of these papal documents on the Rosary. Later popes might stipulate a slight change or stress a certain aspect, but the essentials of all later teachings are already present in Pius V's 1689 bull.

This October, it is well worth reading these documents of going through them once more.

Better still, take up your beads and pray the Rosary.