This is the day which the Lord has made;

let us rejoice and be glad in it. Alleluia! (Psalm 118:24)

To prepare for Easter, Five Books for Catholics recommended a selection of spiritual writings, literature, music, and art for Lent. Here we explore how some of these are just as helpful for meditating upon the mysteries of Eastertide and assimilating them. You can also find more readings for Easter here and here.

- Sermons for Lent and the Easter Season

by St. Bernard of Clairvaux - O Death, Where Is Thy Sting?

by Fr. Alexander Schmemann - Duccio di Buoninsegna

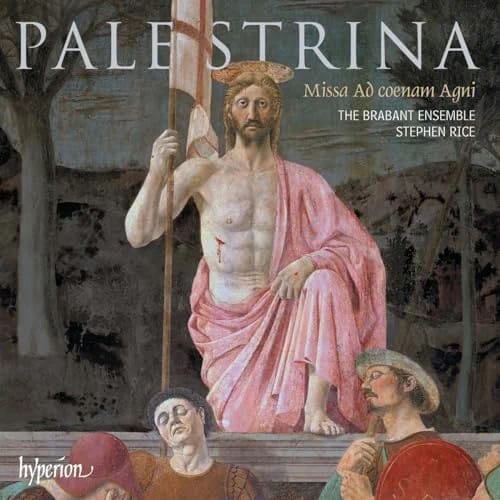

by Cecilia Jannella - Palestrina: Missa Ad cœnam Agni

The Brabant Ensemble, directed by Stephen Rice

1.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a doctor of the Church, has guided us through Lent and Holy. Moreover, the book selected also contains his homilies for Easter.

With Easter, we are no longer burdened with the rigours of Lent and may feel entitled to luxuriate in Christ’s triumph over sin and death. However, much like St. Paul, St. Bernard reminds us that our baptismal participation in Christ’s Resurrection entails and demands a life of virtue and sacrifice.

Indeed, Bernard’s recurring concern throughout these sermons is that we neglect to conform ourselves morally with the mysteries celebrated in the Easter liturgy. Should we be guilty of such neglect, we are living as if Christ had never been born, suffered, died, or risen from the dead.

“For some Christ has not yet been born, for some he has not yet suffered, for some he has not up to now risen. For others he has not yet ascended; for still others he has not yet sent the Holy Spirit.”

St. Bernard, Sermon 4 On the Resurrection of the Lord

Christ, who humbled himself to take on the condition of a slave (Philippians 2:6-7), has not been born for us if we still strive after earthly ambitions and honours. He, who endured hardship and conquered death by dying, has not suffered yet, if we still fear death and avoid hardship. He has not risen if we are anxious about doing penance. He has not ascended if our devotion fails in moments of spiritual desolation.

Nevertheless, Bernard's exhortation to Christian asceticism is predicated upon our condition as new creatures and partakers of Christ's Resurrection.

"Then, as Christ rose from the dead by the glory of the Father, so you too may walk in newness of life."

All in all, Bernard's sermons bring home the practical implications of the mysteries we celebrate at Easter and how Christ's Resurrection must make a real difference in our life.

2.

In the run-up to Holy Week, one of the books surveyed was Great Lent by the Orthodox priest and theologian, Alexander Schmemann. Easter is the right time for reading another of his books, O Death, Where Is Thy Sting?. First, this little collection of some of his radio talks takes its title on St. Paul’s great meditation on the Resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15. Second, Chapter Six is a talk on Easter itself.

In this talk, Schmemann addresses the same concern as St. Bernard.

" 'Christ is risen!— Indeed he is crisen!...Yet, no sooner do we hear these amazing words, rejoice in them, believe in them, when suddenly comes the realization that during this festal night, on this radiant day, in fact millions of people do not hear and possibly have never heard them. For so many people these words announce nothing, proclaim nothing. And how many, upon hearing these words, shrug their shoulders in hostility skepticism, and cynicism? How is it possible to rejoice when so many people do not know this joy, turn away from it, and close their hearts to it? And how is it possible to explain those words and move the hearts of such persons?' ”

In brief, Schmemann argues that there is nothing to explain or demonstrate. Rather, such people need to encounter the risen Christ through the liturgy of the Easter Vigil.

"In the Paschal night mankind is offered a foretaste of the age to come, the possibility of entering the kingdom of glory, the kingdom of God. The language of our world has no words to express this revelation of the Paschal night, its perfect joy."

4.

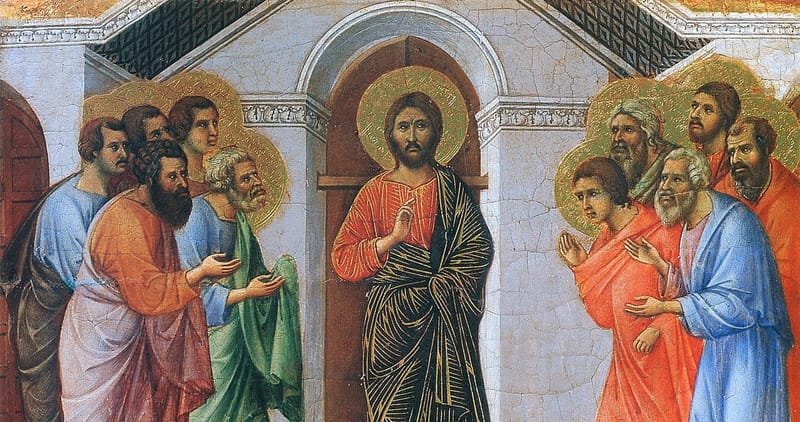

The work of art selected for Lent and Holy Week was the retro of Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà, with the central panel’s paintings of the Passion. However, the same work is just as appropriate for Easter. It also depicts the events from Easter Sunday to Pentecost.

The central panel begins on Palm Sunday and reaches its climax on Golgotha. However, without Easter Sunday, Good Friday would have marked the defeat and downfall of Jesus, not his triumph. Hence, Duccio dedicates the last four of the central panel’s twenty-six panels to Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday.

Furthermore, these four paintings are of the disciples rather than the apostles. First, Christ descends triumphant to hell, where he treads Satan underfoot and releases the just of the Old Testament. Then, on Easter Sunday, the women find the angel sitting on the empty tomb. Third, Christ appears to the Mary Magdalene. Fourth, in a pilgrim’s garb, he accompanies the disciples of Emaus, who have reached their destination and invite him to stay the night with them.

The six paintings of the crowning section, on the other hand, focus on the lives of the apostles between Easter Sunday and Pentecost. Duccio thereby highlights the apostolicity of the Church. We commune with the risen Christ through the testimony, teaching, and sacramental power of the apostles and their successors.

These six paintings are not arranged in chronological order. Rather, on the right and left, Duccio places the events that take place in the upper room, and in the centre the apparitions to the apostles that occurred outdoors.

First, Christ appears on Easter Sunday to the ten apostles present in the upper room. Second, he reappears there the following Sunday and bids the doubting Thomas to put his hand into his wounds. The third painting represents the appearance to the apostles who went fishing at Lake Tiberias; the fourth, Christ’s final appearance to the apostles on the mount of the Ascension. With the fifth, however, we move back to Easter Sunday and Luke’s telling of the risen Christ’s appearance to the apostles in the upper room. Sixth, the Holy Spirit descends upon the apostles in the upper room on Pentecost. Duccio thereby stresses how the sending of the Holy Spirit completes the sending of the Son and is inseparable from it.

Not only is each painting an outstanding depiction of some event from the Gospel. The sequence and Duccio’s thoughtful arrangement of it enables us to see how the salvific events are connected and play out in our lives. As part of an altarpiece, it also brings how the Paschal mystery of the risen Christ is made present sacramentally in the Mass. In the Eucharist, the risen Christ comes to us and communicates his grace, just as he did to the apostles on Easter Sunday.

5.

As for sacred music, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina has been the composer of choice this Lent and Holy Week, both for his prominence within the Catholic tradition of liturgical music, and to commemorate the fifth centenary of his birth.

The recordings selected came from The Sixteen’s Palestrina series. Missing from that excellent series is a sufficiently representative selection of Palestrina’s music for Easter. Instead, the Brabant Ensemble has released one. It includes Palestrina’s settings of Surrexit Pastor bonus (track 6), Regina Caeli (track 7), Haec Dies (track 8), Tulerunt Dominum (track 9), Terra tremuit (track 10), Angelus Domini (track 11), Deus, Deus meus (track 12), Lauda anima mea (track 13), Benedicite gentes (track 14), and Ad cœnam Agni providi (track 15).

You can learn more about this collection from the online programme notes.