Fifth Week of Lent 2025

On each week of Lent, Five Books for Catholics recommends a work for the season. Moreover, it aims to recommend different kinds of work: not just writings that expound Christian doctrine directly, but also works of literature, music, and art that help us contemplate the Lenten mysteries and enter into them. This week’s recommended reading is a guide to the the medieval Italian painter Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-c. 1318/1319). His masterpiece, La Maestà, contains one of the great medieval series of paintings of scenes from the life of Christ.

Duccio di Buoninsegna

by Cecilia Jannella

Around 1308, Dante Alighieri began his Commedia. Contemporaneously, an artist in Sienna, the rival of Dante’s hometown, Florence, began a similarly ambitious work of Christian art. Duccio di Buoninsegna began work on his Maestà.

Duccio was the founder of the fourteenth-century Sienese school of painting. His early work evinces the influence of the Florentine artist Giovanni Cimabue (c. 1240-1302). Duccio may have studied under Cimabue and even worked as an assistant on a couple of the master’s paintings. Even if that were not the case, he was certainly familiar with some of Cimabue’s main works. A group of figures in Duccio’s Crucifixion in the Maestà is modelled on one from Cimabue’s fresco of the Crucifixion in Assisi.

Like Cimabue, Duccio’s paintings are both influenced by the Italo-Byzantine style.

Following the deplorable Sack of Constantinople (1204), many Byzantine icons found their way to Italy, where they were taken as models by local artists.

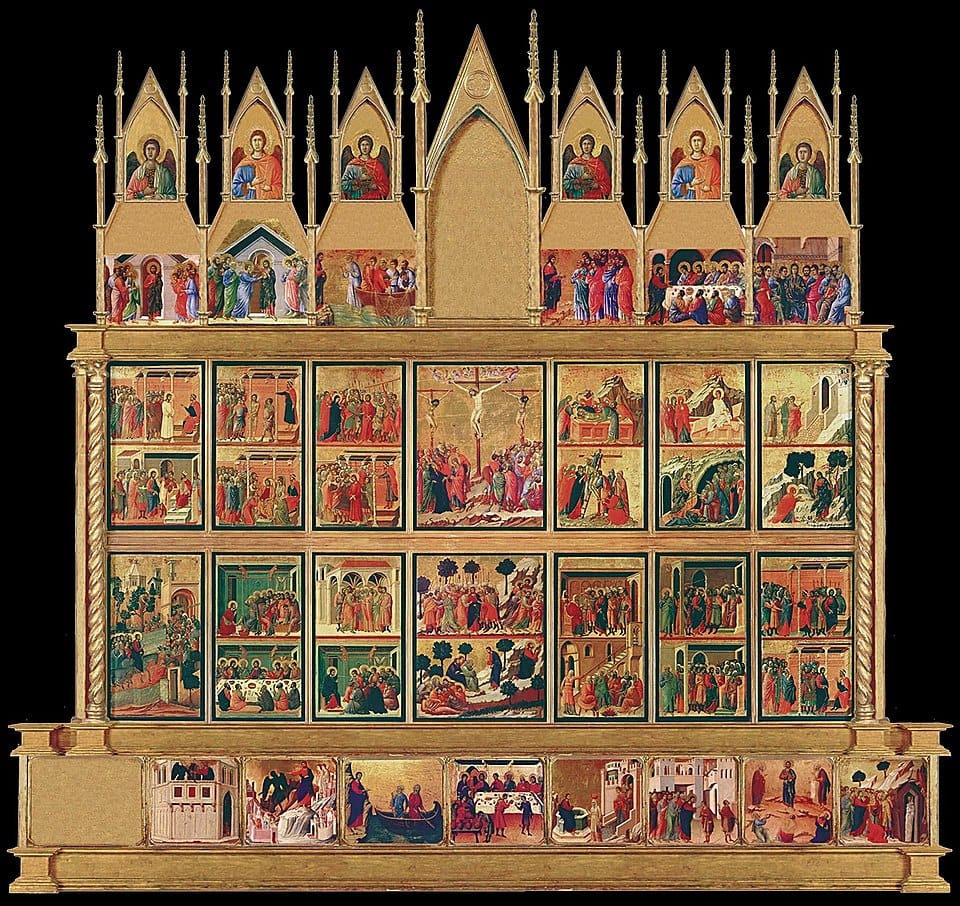

One of the Byzantine formats that which had hitherto been uncommon in the West but which became more widespread in Italy after 1204 were portable panel paintings. Another was the Maestà: a painting of the Blessed Virgin, holding the Infant Jesus, sitting on her heavenly throne, often surrounded by angels or saints. The Maestà genre was influenced by the Byzantine icons of the Theotokos. Duccio’s is the most celebrated instance of the genre.

In October 1308, if not earlier, Duccio was commissioned to produce an altarpiece for the Cathedral of Sienna. At the same time, the contract drawn up for the commission made Duccio swear on the Gospel to respect the agreed upon terms “in good faith, and without fraud.” It also stipulated that he must paint the work entirely in his own hands, to the best of his ability, without any interruptions, and work exclusively on it until it was completed. There was a motive for such detailed, rigorous stipulations. Duccio’s notoriety preceded him. The city archives contain records of fines imposed upon Duccio for his failure to pay debts, and even one for an unspecified recourse to witchcraft. Hence, when commissioning him to paint the Maestà, the Cathedral authorities knew that they needed to keep him on a tight leash. At the same time, by entrusting such an important commission to him, they showed a deep appreciation and esteem of Duccio as an artist. They also acknowledged the sincerity of his faith.

On 9 June 1311, the completed work was transported in procession to the Cathedral, with pipes and drums, by the bishop, clergy, civic authorities, and people of Sienna. The procession was primarily religious in character. The people of Sienna were expressing their deep Marian devotion and entrusting themselves to the protection of the Blessed Virgin. To a lesser extent, the procession may have been a celebration of the city’s religious and cultural vitality, given expression in Duccio’s magnificent altarpiece.

"Mater Sancta Dei sis causa Senis requiei. Sis Ducio vita quia pinxit ita."

"Holy Mother God, may you bring peace to Sienna and life to Ducio, who has so painted you."

Unfortunately, the Maestà was dismantled clumsily in 1771 during remodelling of the Cathedral’s altars. Not only was the altarpiece damaged, but the paintings were separated, with some subsequently sold off to private collectors, and ending up in a variety of museums. As a result, the work is not longer extant or viewable in its entirety. Moreover, the parts that are viewable are housed in museums. This defeats the purpose of the work, which was meant to lead the faithful into a deeper participation of Mass and the mysteries it makes present.

"“The believer of today, like the one yesterday, must be helped in his prayer and spiritual life by seeing works that attempt to express the mystery and never hide it.”

John Paul II, Apostolic Letter Duodecim saecula

While Duccio’s altarpiece is called the Maestà, that title is a synecdoche. The painting of the Virgin is simply the central panel of the recto. Both the recto and the verso contain an array of paintings from the life of the Christ and the Blessed Virgin.

In the Maestà itself, the enthroned Madonna holds the Infant Jesus and is surrounded by angels and saints. To her right, are Saints Peter and Paul, followed by Saints Martha and Apollonia. To her left, are Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, followed by Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Agnes. Above these saints, is the angelic chorus; above them, the other apostles. At the base of the throne are the four patron saints of Siena: St. Ansanus, St. Sabinus, St. Crescentius, and St. Victor.

The eight panels of the crowning section of the recto depicted post-Paschal scenes from the Life of Mary. The lower predella of the front panel, on the other hand, contained seven scenes from the infancy narratives of the Gospel, each flanked by the prophet who foretold it prophets (Isaiah, Ezekiel, Solomon, Malachi, Jermiah, Hosea).

- The Annunciation (National Gallery, London);

- The Nativity (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.);

- The Adoration of the Magi (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York);

- The Presentation in the Temple (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena);

- The Slaughter of the Innocents (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena);

- The Flight into Egypt (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena);

- The Dispute with the Doctors (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena).

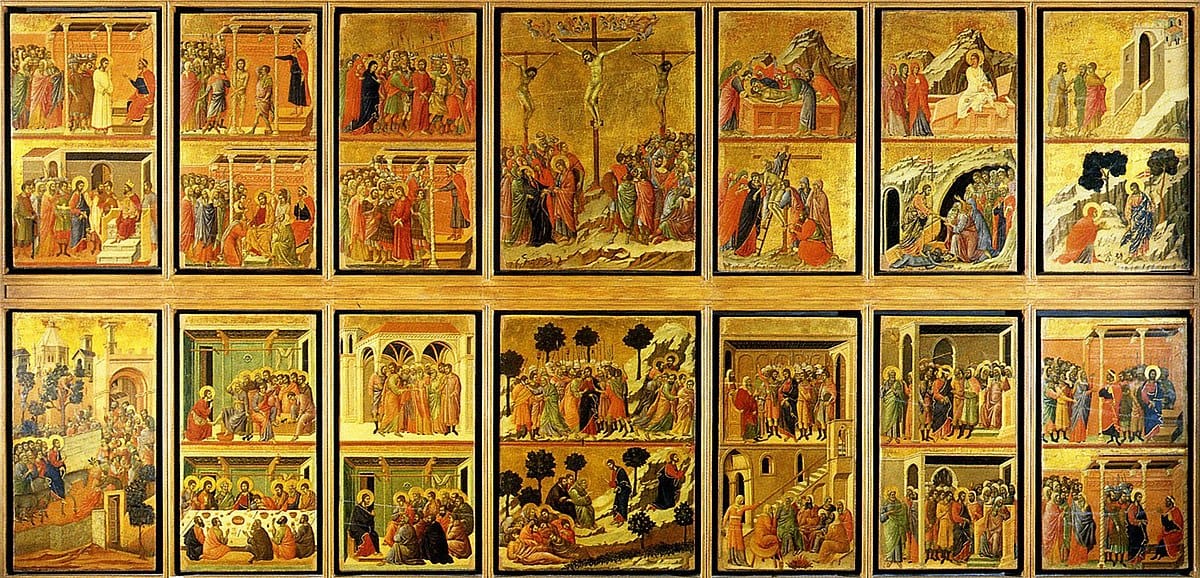

However, it is the verso of the altarpiece that is of interest during Lent and Easter. It comprised forty-three panels depicting Christ’s life and passion.

Whereas the recto would have visible to the assembly during liturgical celebrations—hence the size of the Maestà itself—the verso would have been visible to the clergy in the sanctuary.

The central panel of the verso comprises twenty-six paintings of the events of Holy Week and Easter Sunday. Just as the crowning section of the recto depicted the Post-Paschal events of Mary’s life, the crowning section of the verso represented eight Post-Paschal episodes from the Gospels and Acts, spanning Christ’s appearance to the apostles in the upper room on Easter Sunday to the descent of the Holy Spirit on them there on Pentecost. The predella, on the other hand, depicts nine episodes from the public life of Christ. Perhaps the best known from this set of paintings is the Temptation on the Mountain (Frick Collection, New York).

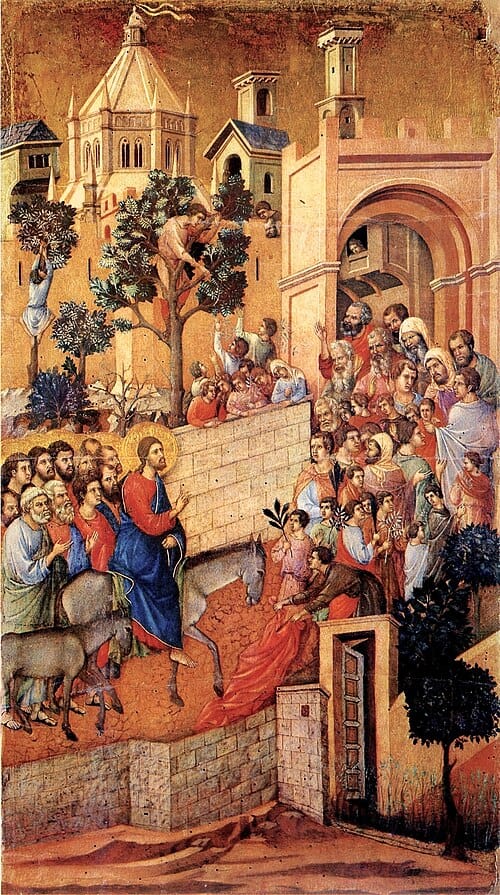

The central panel begins is divided into four registers, with the upper two separated from the lower two by a band. The narrative sequence begins in the lower lefthand corner with Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem on Palm Sundy and end in the upper righthand corner with the disciples of Emanus on Easter Sunday. Significantly, in each of these two scenes, Christ stands before the gateway of a town: Jerusalem and Emaus respectively. As Alastair Smart has noted, the Entrance into Jerusalem is the gateway into the central panel and Emanus the gateway out of it and into the scenes of the crowning section.

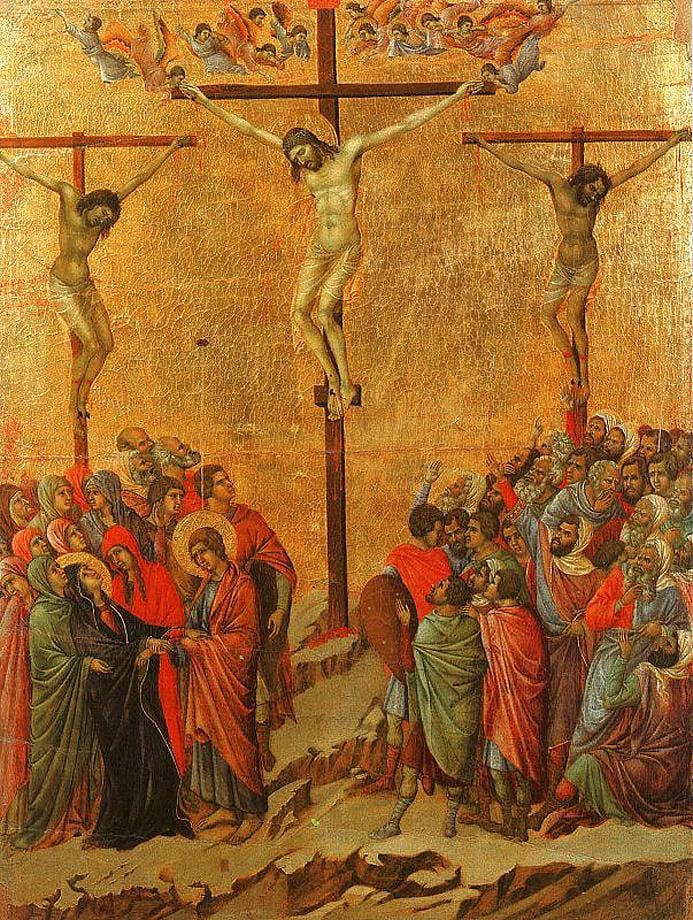

At the centre of the upper register is the Crucifixion, which spans the whole height of the upper two registers and is also one-and-a-half times wider than the other paintings on each side. By positioning and sizing it in this way, Duccio stresses that it is not only the centre and climax of the entire sequence of paintings, but of our Redemption. This is particularly apt as the Maestà is an altarpiece and the Mass makes present the one sacrifice of Christ, our Saviour.

While the influence of Byzantine iconography is palpable, Duccio differs from Cimabue in adopting its canons more freely and wedding them to the greater naturalism, grace, and emotional expressiveness of the Gothic style.

Indicative of this greater naturalism is the care with which he distinguishes the architectural characteristics of the respective residences of Caiphas, Pilate, and Herod. Even more telling are the similarities between the architecture of Jerusalem in the opening painting and that of Duccio’s own Sienna. Duccio thereby indicates that the events narrated in the Gospels are not just events from the past but mysteries in which we continue to participate. We too are either rejecting Christ and contributing to his suffering with our sins or are repenting of our sins, turning toward him and receiving the fruits of his death on the Cross.

Significantly, Duccio’s minimalist representation of Sienna, in addition to the Palazzo Communale and a Church, includes the baptistry, where one became a Christian, a citizen, and a participant in the liturgical mysteries celebrated.

Also apparent in Christ’s Entrance into Jerusalem is Duccio’s use of space to contrast the spiritual state of the characters. A space separates the people of Jerusalem (or Sienna) from the Christ, who approaches with the apostles. Christ and the apostles are composed; the crowd disordered. Similarly, in the Crucifixion, the disciples who mourn Christ stand with greater composure on the right, while the disorderly crowd that scorns him as he hangs on the cross is set on the left.

In the lower register, beneath the three crosses of Calvary, stand three trees of Gethsemane. Duccio uses these to contrast Christ, who stands in the centre, from Peter’s initial impetuousness, as he cuts of Malchus’s ear amid the confusion, from the subsequent cowardice of the apostles, as they take to flight.

In all these scenes, Duccio depicts with far greater freedom than was typical of his Byzantine models the emotional state of the individual characters.

Cecilia Janella’s book on Duccio explains in detail the structure of the Maestà and has colour photos of its various parts. That is why it is the main recommended reading on the work. However, it is also worth reading the more perceptive commentaries of other specialists in fourteenth-century Sienese art, such as those of Bruce Cole, H.W. van Os, or Alastair Smart.

Like all great works of sacred art, Duccio’s representation of the Passion is meant to be contemplated with attention, so that the viewer might unlock its many subtle details and thereby enter more deeply and prayerfully into the mysteries represented. Indeed, sacred art is an essential part of Christian prayer and liturgy, especially during the highpoint of the liturgical year. In this regard, St. John Paul II commented that:

“Authentic Christian art is that which, through sensible perception, gives the intuition that the Lord is present in his Church, that the events of salvation history give meaning and orientation to our life, that the glory that is promised us already transforms our existence. Sacred art must tend to offer us a visual synthesis of all dimensions of our faith.”

John Paul II, Apostolic Letter Duodecim saecula

Duccio's Maestà accomplishes such a synthesis and his depiction of the Passion is well-worth our consideration as we approach Holy Week.