Third Week of Lent

On each week of Lent, Five Books for Catholics recommends a work for the season. This week's is Great Lent: Journey to Pascha by Alexander Schmemann.

You can find further suggested reading for Lent from the archive here and here.

Great Lent: Journey to Pascha

by Fr. Alexander Schmemann

Recently, Andrew T.J. Kaethler, Academic Dean and Associate Professor of Theology at Catholic Pacific College, talked to Five Books for Catholics about the writings of the Russian Orthodox theologian, Fr. Alexander Schmemann. One of the books he selected was Schmemann's Great Lent: Journey to Pascha. It made sense to include it in this year recommendations for the season.

Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983) was a protopresbyter and leading theologian of the Russian Orthodox Church.

He was born in Tallinn, Estonia, to émigrés from St. Petersburg who had fled Russian after the 1917 Revolution. When still a child, his family moved to Paris, where he was educated.

During his preparation for the priesthood at the St. Sergius Institute, he studied under Sergei Buglakov but was also influenced by Catholic theologians such as Jean Daniélou and Louis Bouyer.

He was ordained a priest in 1946. Five years later he moved with his family to the United States to teach, at the invitation of Georges Florovsky, Church history and liturgical theology at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary.

He was an observer at the Second Vatican Council and for thirty years his homilies were transmitted by Radio Liberty to the Soviet Union, where they won the admiration of Aleksandr Solzhenitysn.

He was also active in establishing the Orthodox Church in America, which was granted autocephaly by the Patriarch of Moscow in 1970.

An influential proponent of liturgical theology, Schmemann's writings continue to be widely read and admired.

During the interview with Andrew Kaethler, the discussion turned to Schmemann's book on Lent and its timely lessons for Catholics. Here is the extract from the interview, which will be published later this year.

Is the Schmemann’s Great Lent a good guide for Catholics of the Latin Church even it refers heavily to the Orthodox Lenten liturgy and discipline?

Yes, in large it is. Schmemann says that the purpose of Lent is to soften our hearts. He discusses a beautiful prayer from St. Ephrem the Syrian. Typically, the Orthodox Church prays it as part of their Lenten tradition.

“Lord and master of my life!

Take from me the spirit of sloth,

Faint-heartedness, lust of power, and idle talk.

But give rather the spirit of chastity,

humility, patience, and love to thy servant.

Yea, Lord and King!

Grant me to see my own errors

and not to judge my brother;

For thou art blessed unto ages of ages. Amen.”

Schmemann’s reflection on this prayer is really helpful for all, whether Orthodox or Catholic.

Sloth, he remarks, is the basic spiritual disease. It convinces us that it is impossible to change. It is a deeply rooted cynicism. It results in our faint- heartedness, a state of despondency that makes it impossible to see either good or evil, and then in the lust of power. The lust for power takes the wrong attitude towards others. If God is not my Lord, then everything is all about me. Then idle talk follows.

Schmemann observes that speech is our greatness. No other animal has this great gift. Due to its greatness, speech can also our downfall. Separated from the divine Word, speech becomes idle. How do we counter this? The latter part of St. Ephrem’s prayer explains how: through chastity, humility, and patience.

Chastity is wholeness. It counters sloth and the inability to see the whole.

Humility sees truth for what it is. It sees things as they are because it does not put us in God’s position of or make us the ultimate end. Through it, we begin to see the world for what it is and others for who they are.

Patience consists in an infinite respect for all being.

These three elements—chastity, humility, patience—are brought to the fore in the practices of Lent. They counter sloth, faint-heartedness, the lust of power, and idle talk.

Schmemann thereby offers us a very profound reflection for Lent.

Characteristically, he also tells us that we should not think about Lent as a set of obligations or rules to be followed. Rather, he notes, Lent is the pattern of the Christian life. The Christian life is a fight. It requires the endurance to battle against the powers that be and our own brokenness. Christianity is not a call to relax. Rather, it is call to vigilance and to be always ready for Christ.

Hence, fasting is a great preparation. It reveals to us in a very physical way the reality of Christian life is.

Schmemann also discusses the nature of sin. He has an interesting perspective on it. As he sees it, sin is the rejection of our incredibly high calling. It is a belittling of who we are. Repentance begins with our shock at this rejection and fall, and the desire to return to be sons and daughters of God.

Sin, therefore, is a deviation of our love from its ultimate object: God, who makes us his sons and daughters. Lent, on the other hand, reminds us of what we lack and reveals what we are meant to be.

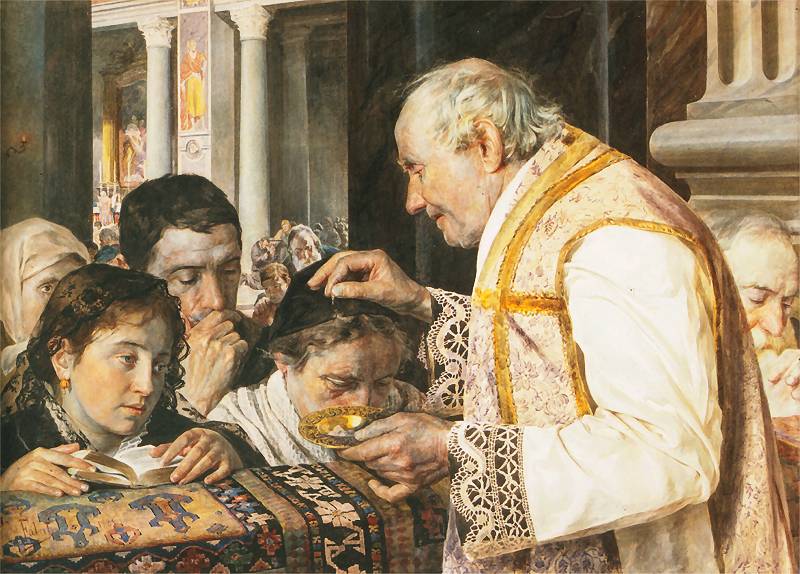

Schmemann also claims that there are two approaches Lent or two kinds of fast. There is the total fast and the ascetical fast. The former is the one that precedes reception of the Eucharist. In current Catholic discipline, we are not to eat for at least one hour before receiving the Eucharist. However, Schmemann notes, total fasts are broken in Lent with reception of the Eucharist. The Eucharistic celebration, which itself is a kind of feast, should always lead.

However, the ascetical fast perdures throughout lent. The Orthodox have a much more demanding Lent than we do. They progressively give up meat, dairy, and so on. They do not give up on the ascetical feast during the Sundays of Lent, even though Sunday is the celebration of the Lord's Day and a kind of feast. The ascetical fasting goes on because it is a purgation. It strips back the things that inhibit us from being fully alive.

This is a very important lesson for us Catholics. Indeed, Schmemann calls out Catholics for making Lent too easy since the Second Vatican Council and lowering expectations to the bare minimum. He insists that we need to have high expectations. We need these demands, partly so that we might realize that we cannot achieve them on our own but only through grace. My Orthodox friends tell me that they will probably fail to observe Lent perfectly. There is a humility that comes with this: the acceptance of one’s littleness and need for God.

These are very important lessons that we in the West can learn from Schmemann.